Why It's Completely Okay To Objectify Men

Ah, the objectification of men.

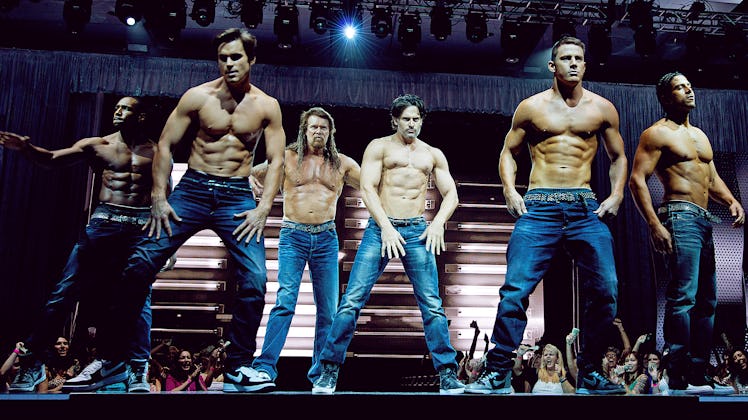

I hear the cries of sexism already. Men see male strippers in "Magic Mike," shirtless photos of sexy male celebrities in Cosmo and 14 photos of hot guys who have great butts on, yes, Elite Daily and proceed to cry about how they, too, experience discrimination on the same levels as women.

They immediately go up in arms about how they feel sexualized, how it's not fair, and how if it's not okay to objectify women, it shouldn't be okay to objectify men either because that's totally a double standard, and that's totally why feminists are hypocritical bitches and blah, blah, blah.

Well, until you straight, white men live in a world in which your objectification leads to excessive victim-blaming, unwelcome catcalling, mortifyingly high rates of sexual assault and rape and having your value in society based exclusively on what you look like, I will continue to exercise my God-given right to objectify you.

Because the objectification of women leads to all of those things. The objectification of men does not.

And that's why it's okay to do it.

"The Male Gaze"

There's a widely-accepted concept in academia called the male gaze, which is the idea that TV shows, movies, advertisements and any other sort of media you can think of are specifically created to satisfy a straight, male audience.

If you've ever noticed a movie camera linger a little bit longer on a female body or advertisements in which women are dressed provocatively for seemingly no reason, that's the male gaze at work.

It creates a culture in which men are always assumed to be the consumer of media. It creates a culture in which men do the looking and women are looked at, in which men are the subjects and women are the objects.

Since men are literally in control of the majority of media behind the scenes, the concept makes a lot of sense.

According to a report by the Women's Media Center, a non-profit organization founded by Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan and Gloria Steinem that tracks female progress in the media industry, women only directed 28.7 percent of top-grossing films in 2012 and only accounted for 23 percent of creators, 24 percent of executive producers, 38 percent of producers, 30 percent of writers, 11 percent of directors, 13 percent of editors and 2 percent of directors in photography of broadcast, cable and Netflix television shows in the 2012-2013 season.

All of these media industry leaders dictate what stories are told in the media and how exactly those stories are told. So, because significantly more men create the stories, significantly more men control the stories -- and, therefore, control the gaze.

There's no such thing as a "female gaze" in our society. Women never do the looking, except when we go see "Magic Mike," browse through the hot guys of Cosmo and giggle over which dude has a nicer ass on the Internet -- in other words, except when we objectify you!

See how this works?

How the male gaze works in society

The male gaze doesn't just exist in popular culture; it exists in everyday life.

Women learn from a young age that a compliment like "You're beautiful" means way more than a compliment like "You're a good person." Everyone gasps in horror if a woman is called ugly, yet chuckles in amusement if a woman is called a bitch, as if insulting her appearance is so much worse than insulting her actual character.

A woman's appearance is the most important thing about her. Her worth is based almost exclusively on what she looks like, how youthful she looks and whether or not she's fuckable.

Amy Schumer's wonderful sketch, "Last Fuckable Day," illustrates this concept perfectly: As women age -- as their skin becomes more wrinkled, their hair becomes drier and greyer and their body loses its lust factor -- they "expire," much like milk, medicine, makeup, credit cards or a driver's license. Much like, well, objects.

This objectification leads to us not being seen as living, breathing human beings but as things, as pieces of property, as something that someone else can take ownership of, claim as theirs and define.

And society doesn't hesitate to let us know our worth is defined by someone else -- specifically, by men.

Because when a woman's worth is defined by how beautiful she is and how sexually desirable she is, it's another way of saying her worth is defined by how much male attention she receives and how much men want to fuck her -- how much she's satisfying the male gaze.

Men don't operate this way. Men don't live to satisfy a so-called female gaze.

On a societal level, a man's worth is defined by way, way more than just his hotness and fuckability, so when we objectify a man, we do nothing more than just make an innocent comment on those two things.

Why a comment on a woman's appearance isn't just a comment, but a comment on a man's appearance is

Women don't live in a world in which a comment on our appearance is just an innocent comment. We live in a world in which a comment on our appearance is systematically engrained into society's attitude towards us.

It's used as a way to measure our value in society, as a means through which our entire identity is defined.

In her piece "You Can't Tell the Attorney General She Has an Epic Butt, But Here's What You CAN Do," Lindy West gives a perfect example of what a comment on a woman's appearance can mean in different circumstances and how the meaning behind a comment differs between women and men:

If you are friends with a woman in your office, you two are hanging out in the break room, and you notice that she's gotten a fetching new haircut, it's completely normal to say, 'Hey, Cheryl, righteous haircut.' But, say, if you are in the middle of a meeting, and Cheryl has just presented her quarterly report to the board, it is not appropriate to raise your hand and say, 'I'd just like to point out the flattering way in which Cheryl's blazer nips in at the waist.' Can you see the difference? One is giving a high-five to a friend in a relaxed, unprofessional setting. The other is derailing and devaluing a colleague's professional contributions; drawing attention to the fact that she's a woman in the board room, not a person in the board room; and reminding her that her primary utility, in your eyes, is as a decorative and/or sexual object.

West continues:

Imagine if every day you came into work, and your boss said, "Really fillin' out those pants today, Jerry," and he never said anything else. Do you think you'd eventually mention it to HR? Well, now imagine that "Really fillin' out those pants today, Jerry" was built, systemically, into the entire culture's attitude toward you from birth onward.

A man's appearance doesn't define him nearly as much as a woman's appearance defines her, so commenting on his appearance has an entirely different meaning than commenting on her's.

When you comment on the female body, like West says, it can reinforce the deeply ingrained idea that a woman's appearance is all that matters about her and that her sole purpose is to be something for men to look at (see: male gaze). The fact that we are people doesn't matter. Nothing matters. Except the way a man's dick feels about us.

On the contrary, when I comment on the male body, I really do nothing more than that. I observe it, say a few words about it, and then, since it has no real effect on the status of who he is as a person, I kind of just move on.

In fact, when a New York Magazine article asked if men can ever be fat-shamed, the answer, ultimately, was no.

As Kat Stoeffel writes in the piece, tabloids reporting on Leonardo DiCaprio's weight gain did little to affect his identity -- his extra pounds were "no more or less damning than the hideous graphic T-shirts and newsboy caps he wears" -- whereas reports of Jessica Simpson's weight gain warranted a dramatic, emotional talk show segment dedicated to her "weight-loss journey."

That's why objectifying a woman carries a heavier, more noteworthy meaning. When you objectify a woman, you perpetuate the idea that her worth lies exclusively in her appearance. When I objectify a man, it's just... fun.

And that's why it's okay to do it.