Why Rape Kits Are Crucial In The Fight Against Sexual Assault

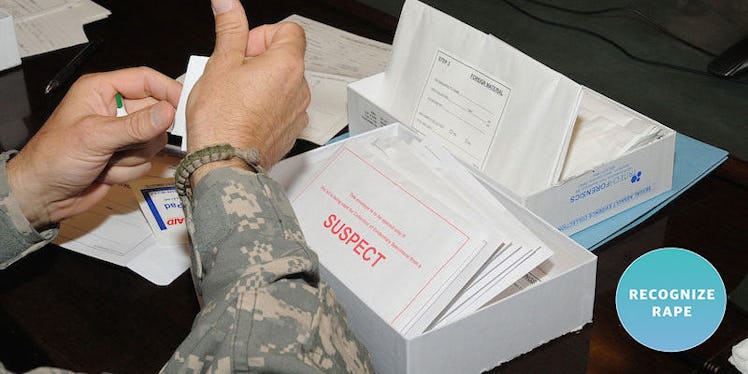

There are few things more important in the fight against sexual assault than rape kits. A rape kit is a container filled with important evidence collected from the scene of a rape crime.

It includes clothing, personal belongings and forensic evidence from the survivor's body, such as blood or DNA that could belong to the attacker.

Simply put, however, the public doesn't understand the importance of rape kits. As a result, many survivors don't even bother getting rape kits and thousands of completed rape kits sit unanalyzed in police departments, hospitals and rape crisis centers.

This, of course, is doing a huge disservice to the thousands of survivors whose rapists don't get brought to justice.

In order to solve this problem, Rebecca O'Connor, vice president of Public Policy at Rape Abuse And Incest National Network (RAINN), wants to change the public's perception of rape kits.

If a survivor reports their rape and goes to trial, the DNA found in a rape kit is vital in putting an attacker behind bars.

"DNA is really one of our most critical anti-rape tools as a country," O'Connor says. "As the science develops and as our ability to understand the nature of these crimes develops, it becomes more and more important in the realm of the 'CSI effect,' where juries expect to see DNA."

DNA is really one of our most critical anti-rape tools as a country.

DNA also plays a massively important role in catching repeat offenders.

Lots of rapists, O'Connor says, are "by and far not the strangers in the bushes," but are in fact serial criminals. This means their DNA could be in multiple survivors' rape kits.

O'Connor says a huge part of her job is convincing the public that merely relying on survivors' knowledge of who raped them — the sort of "he said/she said" method, as O'Connor put it — isn't enough to stop rapists.

She explains,

Back in the old days, even if they had the capacity to test [a rape kit], if they had the science and tools to do it, they may say 'Ah, we don't need to test this evidence because we already know who did it; she said it was her boyfriend, her husband or whatever.' A lot of our job is explaining to the public, lawmakers, etc., to say, 'No, no, wait a minute. Jane may know her husband did it, but at the same time, does Jane know that her husband who's a truck driver is going on a nationwide crime spree?'

If rape kits continue going untested — in other words, if the DNA and blood samples aren't sent to an accredited lab to get analyzed and stored as evidence — serial offenders won't get caught.

To help the public further understand the importance of rape kits, RAINN, along with many other organizations, takes part in the Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI).

Administered by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, SAKI educates facilities around the country that store untested rape kits about how to handle their backlogs. It's estimated there are hundreds of thousands of untested rape kits in the US.

Through this initiative, O'Connor has found there's no one-size-fits-all answer to dealing with facilities that have untested kits.

She says,

Some of them are starting from ground zero and have no idea where to step first. It [also] comes down to [a question of], 'How do you define whether or not a rape kit was submitted?'

O'Connor says another very important issue is making sure survivors "retain empowerment and a voice" in the process of submitting their rape kits.

Submitting a rape kit after a sexual assault is a traumatic experience. Lots of survivors might (understandably) want to shower or change their clothes after an assault instead of going through the process.

Then, there's the question of reporting.

It's not necessary for survivors to report their rape just because they got a rape kit done. But if a survivor does choose to report, that experience can be even more traumatic, since many survivors experience harassment, slut-shaming and victim-blaming after reporting.

To quell other survivors' fears about reporting, O'Connor works with those who are ready to share their stories with the public.

"We work tirelessly with survivors who are at a place where they want to be a part of the solution on this and want to share publicly what works and what didn't work [for them]," she says.

Regardless of whether or not survivors end up reporting, however, O'Connor maintains that her work on untested rape kits is not in vain.

She explains,

We and other organizations have come to a place where we adopt a test-all-reported-kits mentality. We're always maintaining that just because a kit is sitting unanalyzed doesn't mean that the process isn't working per se. The victim just may not be ready to report, and we have to respect that, as painful as it is for many actors in the system.

O'Connor believes strongly in the indirect impact of what RAINN and journalists who report on stories like these do. She wants survivors to know there is work being done to ensure that rape kits are an important part of the justice system.

"Even if [survivors] don't get justice in the traditional sense of the person going behind bars, they feel validated just knowing that something came of what they went through."

Citations: USA TODAY, RAINN, SAKI.org, Bustle, End The Backlog