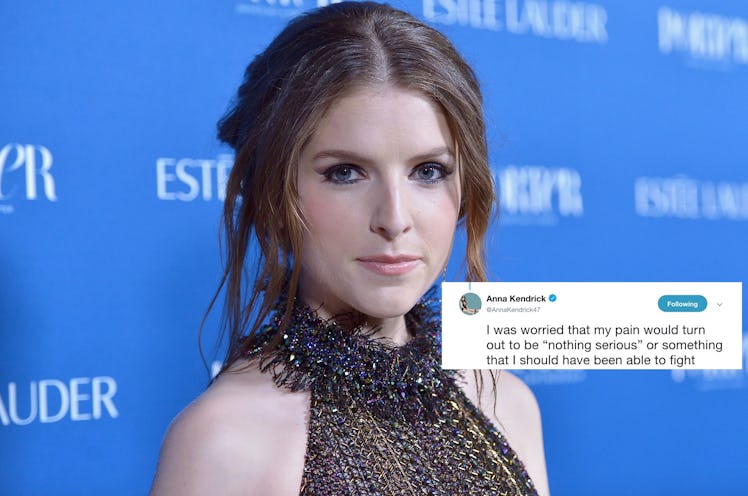

Anna Kendrick Made A Great Point About Questioning Your Own Pain After Battling Kidney Stones

Two weeks ago, I had surgery on my ankle. The surgeon was incredibly casual about the procedure, and told me I'd be able to "walk right out of there." When I woke from the anesthesia, though, I immediately realized I wouldn't be walking that day, or for days afterward. When the pain persisted and the stitches began to open up, I questioned myself before calling my doctor, assuming I was being overly cautious or dramatic. Anna Kendrick's tweet about her kidney stones captured exactly what I felt after my own surgery, and what many women experience when taking care of their health.

In her tweet thread, Kendrick talked about how she was hesitant to seek treatment for the pain that would turn out to be kidney stones. "I was worried that my pain would turn out to be 'nothing serious' or something I should have been able to fight through," she wrote.

Fortunately, based on these tweets, Kendrick seems to be recovering well from her kidney stones. In one tweet, she even took time to personally thank, by first name, a team of attentive women doctors and nurses who cared for her during her hospital stay and helped her navigate the experience.

But Kendrick's instinct to first question whether her pain was even valid is both common, and reinforced by gender biases in the medical community, such that, per The Atlantic, many doctors simply do not take a woman's pain — especially a woman of color's pain, which I'll get into more in a bit — as seriously as that of a man.

First of all, there seems to be an inherent pressure for women to take care of things on their own rather than "bother" someone, an inclination that I can certainly relate to, and that has been demonstrated in research. According to a study published in The Clinical Journal of Pain, a medical journal that covers research on pain management, one of the factors that apparently tends to influence a woman’s likelihood of seeking medical care for her pain is a predisposition to “resilience or positive regard for their ability to handle the problem" — in other words, a concern that she might potentially inconvenience other people by seeking help, and the thought that perhaps she can handle the pain on her own. Men, on the other hand, the same study argued, tend to be more motivated to seek health care by “a negative attitude about the [health] condition in terms of its harmfulness, loss or threat."

But even after medical procedures take place, the inequality persists: Women, as well as people of color (regardless of gender, it seems), are oftentimes not given the same pain management tools that men, and white people in general, are, according to the findings of a study published in Research in Nursing and Health, a journal devoted to research that informs the practice of nursing and similar health disciplines. In the study, the researchers surveyed 101 male and 79 female patients (40 of whom were people of color) after they'd had appendectomies without complications, and found that men received significantly more narcotics after the operation than women did, and non-white patients received less pain medication than white patients.

In another study, published in the medical journal Annals of Emergency Medicine, researchers evaluated whether black patients with minor bone fractures may be less likely to receive pain medication than "similarly injured" white patients. After studying 217 patients — 127 of whom were black and 90 of whom were white — the researchers found that only 57 percent of the black patients who were treated for fractures were given pain medication, while 74 percent of white patients with "similar injuries" were given the same medication.

Race is an inescapable factor in how patients receive medical care. As per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) 2016 data, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births was 11.4 for non-Latinx black babies and 4.9 for non-Latinx white babies — a staggering difference of almost threefold.

Even a celebrated elite athlete like Serena Williams wasn't believed when she told doctors that something was wrong. In an interview with Vogue, Williams described the complications that took place after her C-section. When she realized she was having trouble breathing, she asked a nurse for treatment for what she believed to be a pulmonary embolism. At first, per her story as told to Vogue, the nurse assumed she was just confused because of her pain medication. But upon further examination, they found that she was, in fact, experiencing several blood clots in her lungs. “I was like, listen to Dr. Williams!” she told the outlet.

“Actual institutional and structural racism has a big bearing on our patients’ lives, and it’s our responsibility to talk about that more than just saying that it’s a problem,” Dr. Sanithia Williams, an African-American OB/GYN in the Bay Area and a fellow with the nonprofit organization Physicians for Reproductive Health, told The New York Times.

As Dr. Williams said, talking about these issues is just one step toward solving the problem. If you're interested in doing something more, one way to get involved is to support organizations that specifically provide people of color with professional opportunities in the health care industry, such as the National Dental Association, the National Hispanic Medical Association, the National Medical Association, the National Black Nurses Association, and the Asian American Pacific Islander Nurses Association, as well as organizations that support similar opportunities for women, like the American Medical Women’s Association and the National Women's Health Network.