As A Young, Disabled Voter, My Life Is On The Ballot — Why Is It So Hard For Me To Vote?

On Election Day 2018, I was lying on my bed in my New York City apartment, in pain and wondering how I was going to vote. I had applied for a mail-in ballot, but it never arrived. Prior to my flare, I had told myself I would just deal and vote in person, but my body had other plans for me. As a young, disabled woman, my life and health depend on voting on the policies that will affect me. Young, disabled voters look ahead at a lifetime of being impacted by issues like high health care costs and climate change, and our voices need to be heard. So, why is it so hard for us to actually vote?

I voted in my first election in 2016 when I was 18 years old, first in the Massachusetts Democratic primary and then in that year’s presidential election. But between the primary and the general election, I was in a car accident that led me to develop systemic urticarial vasculitis, a rare autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation of my blood vessels. While I have always been a politically-engaged lefitist, after my accident, I became acutely aware of how political issues affect my everyday life.

For young, disabled voters, not having a say in an election can literally be life and death.

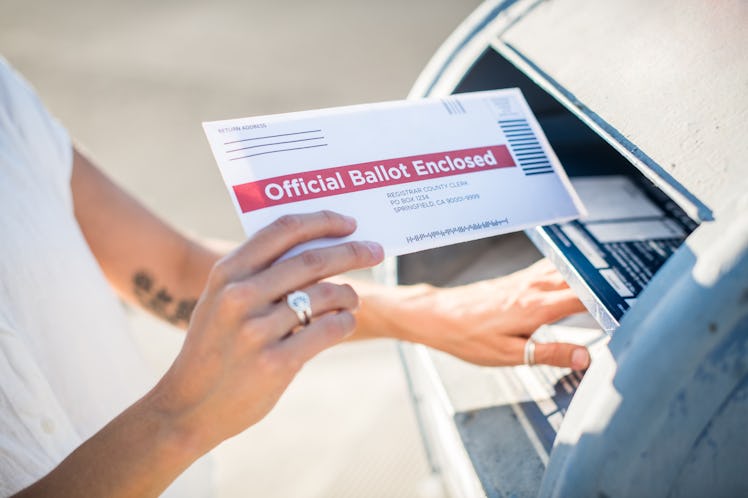

Since becoming chronically ill, I’ve also learned how inconsistent voting access can be for people with disabilities. In the 2016 election, I was studying internationally. I got my ballot by email, printed it out, and mailed it back without any problems. But in 2018, my ballot never arrived, and the same thing happened in the 2020 primaries. Thankfully, I got my ballot to vote by mail in the November general election, but the process should not be this disorganized.

Younger voters, traditionally, aren’t expected to vote. While millennial voter turnout rose from 2012 to 2016, per the U.S. Census Bureau, still, less than 50% of registered millennials made it to the polls in 2016. In 2020, Gen Z is expected to make up only about 10% of the electorate, in large part because many are still too young to vote. Disabled voters of all ages are even more underrepresented — in 2016, people with disabilities made up about 17% of eligible voters, or over 34 million people, according to a report that year from Rutgers University researchers. But less than half of them, only 16 million, made it out to vote. The gap in access was largest for young voters in the 18- to 34-year-old range, meaning young, disabled voters are most likely to be impeded in accessing their right to vote.

For young, disabled voters, not having a say in an election can literally be life and death. The leader in the White House has a huge impact on policies like access to affordable health care. Young people with chronic health issues need affordable health care so they’re not always struggling to find endless amounts of money for medication and treatments just to live. Although neither presidential candidate supports Medicare for All, I think Americans could push Vice President Joe Biden to support it because of his existing desire to expand the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Even issues that aren’t obviously associated with disability rights, like climate change, can have a huge impact on young, disabled voters: A 2020 report from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights found climate change will exacerbate the inequalities disabled people face, like poverty. The same report found climate change can also have a detrimental impact on health, which could affect the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses or disabilities. For the youngest voters, the decisions made today will directly impact how hard we struggle for the rest of our lives.

The barriers standing in the way of weighing in on those decisions can be overwhelming. According to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, disabled voters have the right to vote independently, have accessible polling places and machines, seek assistance from poll workers trained to use those machines, and bring someone to help them vote. According to the Americans with Disabilities Act’s (ADA) website, there are five laws — the ADA, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act of 1984, the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, and the Help America Vote Act of 2002 — that protect disabled voters’ rights.

But the on-paper right to accessibility isn’t always enough. A U.S. Government Accountability Office report found two-thirds of polling places inspected on Election Day in 2016 were inaccessible. In 2020, Blind voters in Texas, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maine, and Virginia sued their state election boards, alleging inaccessible paper absentee ballots would force them to vote in person, or force them to use assistance they don’t want. According to a September 2019 article from the National Conference of State Legislatures, there are 19 states that don’t allow for the electronic transmission of ballots, meaning Blind voters in these states aren’t able to use screen readers and other accessibility devices to fill out their ballots independently.

Even worse, thousands of disabled people may not be allowed to vote at all due to their disability. As of 2018, 39 states and Washington, D.C. allow judges to strip a disabled person’s right to vote if they are deemed “incapacitated” or “incompetent,” per Pew Trusts.

Hopefully, those in charge of running the 2020 election will see the accessibility barriers disabled voters face.

Barriers to voting access can be fixed when there is the will to do so. The New York Times reported in September 2020 that nearly 100,000 voters in New York City, primarily in Brooklyn, had received erroneous absentee ballots for the November election, with incorrect personal information that would disqualify the ballot. Disabled voters like me know these kinds of problems — like my 2018 situation — have always happened, but in this case, it affected abled voters too and caused public uproar. Later that month, the New York Board of Elections promised to reissue the flawed ballots.

More work is needed to increase voting access for young, disabled people. The American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD) held National Disability Voter Registration Week this past July, and also partnered with When We All Vote to create an online voter resource hub. While these kinds of actions are great, disabled people may not know about these tools. My 95-year-old grandmother in Florida receives calls from one of the many organizations providing voter assistance to the elderly — younger disabled people deserve to have this level of outreach, too.

Hopefully, those in charge of running the 2020 election will see the accessibility barriers disabled voters face. Maybe by the 2024 election, absentee ballots will be sent to everyone who requests them without errors, Blind people will be able to vote independently by the method of their choice, and disabled people who prefer to go to physical polling locations will find those locations as accessible as they are mandated to be by law.

As difficult as it’s been so far, I will keep voting in elections. Especially now, during the COVID-19 outbreak, we need comprehensive health policies like Medicare for All. Many young people may develop long-lasting health conditions after contracting COVID-19, increasing the need for resources to manage health and disabilities. This election is life and death for disabled people like me, and our voices deserve to be heard.

Your voice matters. So does your vote. Make sure both are heard and counted in the 2020 election by registering to vote right now.