This Is Why Women Get Abortions After 20 Weeks — And Why The GOP's Law Is Cruel

Rachel Goldberg and her husband were told her blood work was fine at 16 weeks of pregnancy in 2015. This was her first pregnancy, so she didn't think anything of it when the tech asked about the blood work results during her 20-week ultrasound. She and her husband were just excited to get the pictures so they could tell their friends about the pregnancy. Then the tech called the doctor in, who told Rachel she was seeing abnormalities in the fetus and referred her to a specialist.

"I just remember just kind of staring at her, because I really just don’t remember having any cohesive thoughts; I just didn’t know what that meant," Rachel says in an interview with Elite Daily.

After seeing a specialist for an intensive ultrasound and an amniocentesis, Rachel was told her baby wasn't developing properly.

I didn’t want my husband to lose his child and his wife on the same day

"Our doctor said that he wasn’t sure [the baby] would survive, and [the doctor] wasn’t sure that even if he did survive that one of the surgeries he would need wouldn’t kill him, and even if he did survive birth and then multiple surgeries, he wasn’t sure if all of his organs would be connected or what kind of quality of life he would have or anything like that," she says.

"It became very obvious that even if [the baby] lived, he would clearly suffer, and the only reason we would continue the pregnancy is because we really wanted a baby, not because he would have a good quality of life. We decided that we really couldn’t ask him to suffer for our needs."

Meanwhile, the pregnancy was high-risk to Rachel's own medical safety.

"I didn’t want my husband to lose his child and his wife on the same day, so we decided to get an abortion," she says.

These are the decisions Republicans in Congress are trying to prevent.

This week, House Republicans proposed and passed a ban on abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy. A similar bill is now in the Senate. It does not look like the Senate will be able to pass it — it would need 60 votes to pass, and there are only 52 Republicans in the Senate. Senators are expected to vote largely along party lines.

But the message the proposal sends is clear, and it's harmful, and it's cruel.

"What does that say to the average American at home?" asks Dr. Jennifer Conti, a clinical assistant professor in obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University and a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, in an interview with Elite Daily. "To someone who doesn't work with these women and see what it’s actually like in real life … this is really deceiving."

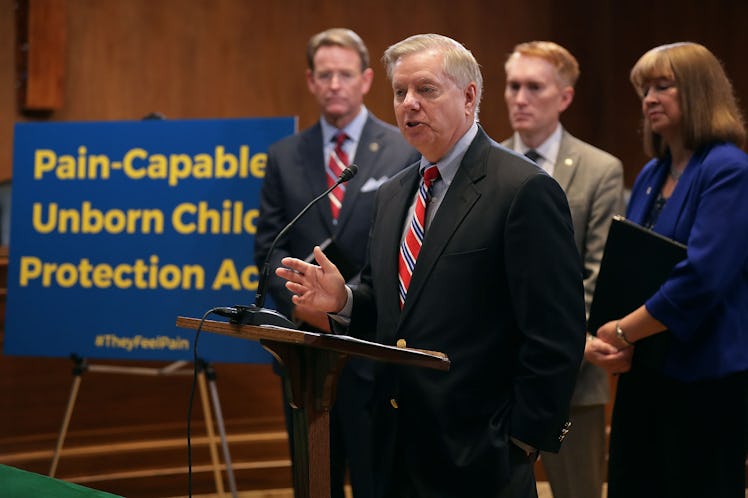

The Republicans are calling their bill the "Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act," arguing that fetuses after 20 weeks' gestation can feel pain. This is a myth as actual research, such as a report from the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Medical Association, shows. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) also notes that science does not support the fetal pain argument.

"In reality, it’s not based in science, and that’s really misleading to the American public," Conti says.

To use these kinds of abortions to score points is just ridiculous.

The House Republicans aren't doing this because of reality. They're doing this to push an anti-abortion agenda in any way possible.

The reality is that only 1.3 percent of all abortions in the United States happen after 21 weeks' gestation, according to the Center for Disease Control's latest report from 2013.

"They're happening for a variety of reason that oftentimes are emotionally charged or medically complicated," Conti says.

"The most common reason I see is for genetic or fetal abnormalities," Dr. Anuj Khattar, a family medicine specialist and a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, tells me. This includes fetuses that are missing a brain or internal organs as well as those with cardiac abnormalities and lethal genetic issues. "Oftentimes [these issues are] not discovered until those ultrasounds that occur around 18-21 weeks."

There are also social reasons why a woman would seek an abortion after 20 weeks. Khattar had a patient a few weeks ago, for instance, who wasn't able to get to a clinic because she was in an abusive relationship and her boyfriend wouldn't let her go. She was finally able to see Khattar for a procedure after her boyfriend was put in jail. She was past 20 weeks.

According to Khattar, there have been patients who lost their job and health insurance, there are patients who didn't know they were pregnant, and there are patients using substances who realized they were not in a place to be a parent.

Then you have to consider the legal blockades. States across the country have been passing laws to make it more difficult for women to obtain the medical procedure of an abortion — making it more time-consuming, further away, more expensive, and so forth. After anti-abortion laws were passed in Texas, for instance, women in Dallas were delayed as long as 20 days for an initial consultation in 2015, according to a report by the Texas Policy Evaluation Project.

"Our society isn’t really created with people to have the best access to health care, and unfortunately people get delayed in ways you don’t want or expect," Khattar says.

Rachel and her husband were blocked by laws as well.

She didn't meet the requirements for an exception to get an abortion after 20 weeks under Missouri law, where they lived. So they had to drive to Colorado for the procedure. The doctor they saw there — one of the few in America who provides abortion at that point in a pregnancy — wasn't in her insurance network, and her insurance company refused to cover the cost of the procedure, which was $10,000. Rachel and her husband had to take out a loan to pay for it.

"I have a place of privilege, I come from a middle class family, I’m white, I’m able to get a bank loan, my husband and I work, and it was hard enough for us to obtain an abortion when we needed one," she says. "I can't imagine what it would be like for people who don’t have those resources."

Rachel chose to tell her story when Missouri started debating a ban on abortions after Down syndrome diagnoses. She has testified to state legislature about her experience and shared her story with the 1 in 3 Campaign. That proposal made her angry, just as the GOP's current federal proposal makes her angry.

"Abortions done this late in pregnancy are for severe medical reasons, or because the mother couldn’t raise the money in time to get an early abortion, or there’s domestic violence, or things like that going on," she says. "To use these kinds of abortions to score points is just ridiculous."

There is a happy ending here: Rachel gave birth to a boy in August.

"My living son would not be here if I wasn’t able to have an abortion, and I probably wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have that choice," she says. "It’s just frustrating that my health care is being used as a political weapon, and that’s all it is."