What We Can Learn About Police Brutality From An NBA Player's Trial

At a time when the football calendar is in full swing and October baseball has begun captivating audiences, the most significant sports story in America this past week ironically involved a basketball player, with the action occurring on a different court.

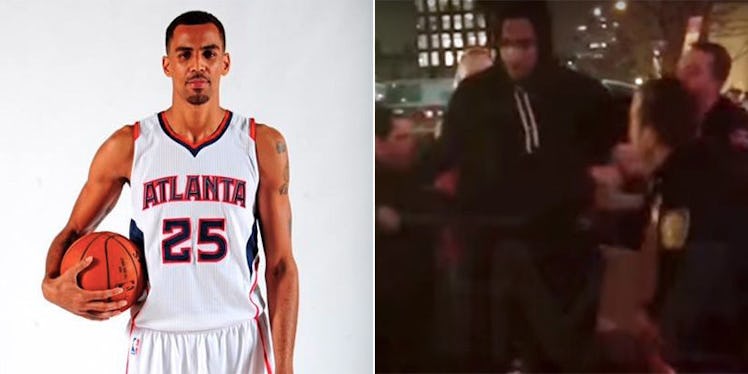

On Friday, the trial of Atlanta Hawks guard Thabo Sefolosha in Manhattan Criminal Court, which stemmed from an April 8 arrest, reached its conclusion.

Sefolosha was facing charges of resisting arrest and interfering with a police investigation, but by the end of the "criminal" trial, reporters couldn't help but note how the case had taken on the image of a civil suit.

Thabo's attorney points out to the jury that at this point this case *feels* like a civil case instead of criminal. I don't disagree. — Lindsey Adler (@Lahlahlindsey) October 8, 2015

More than a couple people have conveyed to me that they believed the NYPD was on trial in this case, or that it was a civil suit. — Lindsey Adler (@Lahlahlindsey) October 9, 2015

It's an unusual occurrence, but it only takes one look at the key details in Sefolosha's case to make it clear why the NYPD would have more convincing to do than the actual defendant.

Sefolosha was arrested near 1OAK nightclub last spring near the scene where NBA player Chris Copeland was stabbed.

The police claim that Sefolosha refused to disperse from the crime scene, which interfered with the officers' work.

Sefolosha, for his part, maintains he was ganged up on by police while he was giving money to a homeless man near a private cab away from the crime scene.

Every significant piece of evidence on show, as detailed by dispatches from the trial by credible media reports, seemed to overwhelmingly favor the defendant's assertion that he was not only wrongly arrested but also a victim of police brutality.

Despite charges of resisting arrest, a fairly docile Sefolosha is shown in one video of the incident being tugged in different directions by multiple officers before he is taken down to the ground, where an officer is shown striking the Hawks player with a baton.

Despite claims it was Sefolosha lunging at an officer that prompted his arrest, you can hear Sefolosha's friends around the 30-second mark of the video lamenting the fact that he was arrested while giving money to a homeless man, as the defense claimed.

Despite charges of interfering with a crime scene, Danny Knobler of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution noted the prosecution did not deny Sefolosha was near his private cab at the corner of 10th avenue when he was arrested, as the defense claimed.

And then there's the topic of how and why Sefolosha exited his encounter with police with a leg injury, which kept the player out of the NBA playoffs and was widely considered a significant detriment to the title hopes of the no. 1 seeded Atlanta Hawks.

Officer Daniel Dongvort testified that Sefolosha told police the injury was suffered before the arrest.

He said this despite the fact Sefolosha was partying at a nightclub before the encounter, played 20 minutes in an NBA game less than 12 hours beforehand and had only traveled with his team to New York to play another NBA game, against the Brooklyn Nets, on the day of his arrest.

okay, this part from the sefolosha trial is just hysterical pic.twitter.com/Wwvb1LRUy7 — El Flaco (@bomani_jones) October 7, 2015

Safe to say, Dongvort's claims were shaky, which made it all the more strange that such a story remained under the radar last week.

Between the fact that a prosecution's defense was reaching near laughable levels against an athlete of relatively high-profile and doing so in a case that falls in line with a nationally-raging debate, there was enough to stir more meaningful conversation on police-civilian interaction.

But even for people who would like to look at these cases conservatively, the let's-get-all-the-facts-before-reacting approach, there's no reason to shy away from this topic now.

The verdict is in.

Sefolosha was found not guilty before the weekend after a jury of six joined for an unsurprisingly short deliberation, given the seemingly one-sided nature of the evidence.

For many, the focus has now shifted from whether Sefolosha is innocent to if he will pursue an actual civil case.

Thabo Sefolosha found not guilty on all three charges opens door for his civil lawsuit against NYPD. Incident jeopardized his career. — Jeff Zillgitt (@JeffZillgitt) October 9, 2015

But there are much more important takeaways from this case than the question of whether or not the city of New York will end up owing a millionaire millions of dollars.

The verdict should instead force us to re-think how we consider cases of potential police brutality. In that consideration, there are a few obvious lessons that cannot be lost.

The first and most obvious is that Sefolosha's exoneration is a direct result of him having the money to prove it and fame to draw attention to it. This was not lost on the player himself.

In a Facebook post published after the conclusion of his trial, the Hawks guard said,

Justice was served yesterday, it pains me to think about all of the innocent people who aren’t fortunate enough to have the resources, visibility and access to quality legal counsel that I have had.

With much of the national discourse on police interaction focusing on the law's treatment of people in low-income neighborhoods, it'd be morally irresponsible not to question how many more people have been denied vindication, and thus how many more officers could have gotten away with acting improperly.

And in considering that question, it'd be near-impossible to avoid reconsidering how much pressure society puts on the police departments to stop the occurrence of cases like Sefolosha's.

Yes, police officers have a difficult job, but the idea that a degree of difficulty should entitle one to both unwavering support and the benefit of the doubt even in the face of legitimate claims of misconduct does not fall in line with the way society generally treats other figures with equally, if not more, important work.

Politicians, too, are tasked with protecting and bettering our lives, albeit in different ways, yet they are still universally scrutinized and held to a high standard.

The numbers indicate such scrutiny of police is not only sorely needed but also in the best interest of everyone. According to a Wall Street Journal study, the 10 cities with the largest police departments in the US paid $248.7 million in settlements that stemmed from cases of police misconduct.

As the report notes, because police departments are self-insured, most of the cost comes back to us, the taxpayers.

not sure why people don’t realize their tolerance of these killings costs tax dollars. https://t.co/wMp0fIqvvF — El Flaco (@bomani_jones) October 9, 2015

Last but certainly not least is the question of race's role in this case, especially considering the optics.

Here is a case in which a 6-foot-7 black man, without breaking the law, got into an argument with an officer 12 inches shorter and ended up in handcuffs with a leg injury.

It's an incident that was described as "pure racism" by Macedonian Pero Antic, a former teammate of Sefolosha's who was arrested with him the night of the incident and is shown in the video above receiving much kinder treatment from police despite having "grabbed one of the officers by the shoulder."

Over a month after former tennis player James Blake was wrongly tackled out of nowhere by an NYPD policeman, and following the verdict of the Sefolosha trial, there's room for a more than reasonable inclination to question why police feel empowered to meet non-violent people of color with violence.

All of these are fair questions to ask, particularly after Sefolosha went out of his way to take his case to trial in search for those answers. The Swiss player was offered a deal that would have only given him a day of community service and six months probation.

Instead, he pursued litigation and the prosecution's case didn't hold up.

But you have to wonder how many more stories like his, involving people of much less fortune, will never be told.